Rusty Method Overloading via. Traits

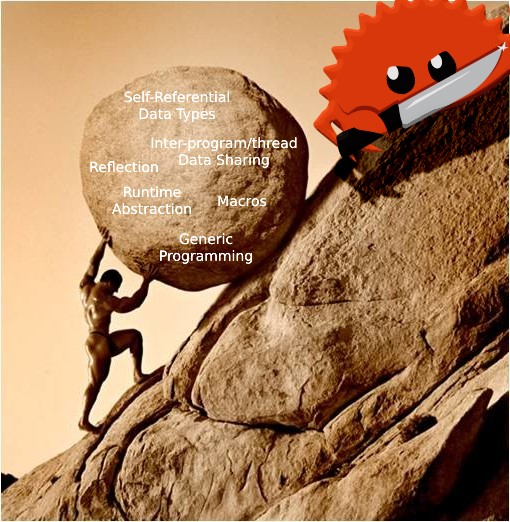

Rust has a reputation for taking concepts programmers are familiar with and turning them on their head, if not discarding them outright! Many are left scratching their heads, asking themselves “why?” as they stumble through yet another seemingly arbitrary, overly pedantic obstacle. Engaged in a sisyphean battle against the language’s strict idioms, what should’ve taken minutes has taken hours!

Anything you can do, I can do better!

One such concept discarded is that of traditional method overloading. Or well, not discarded - more-so re-hashed & realized in a different manner. Opinionated, so to speak. Those familiar with Java, C++, any many other OO languages, will be intimately familiar with the concept of overloading; but for those who aren’t, let’s dive in:

Crash Course in Overloading

Click here to skip this section if you’re already familiar with the concept.

Overloading is a process by which we may define several implementations of a method, each defining a different set of inputs or parameters. It’s something best described via. demonstration - In Java, say we wished to create an (extremely primitive) Calculator, defining several methods for performing arithmetic on an underlying value:

class Calculator {

protected double value;

public Calculator() {

this.value = 0.0d;

}

public void add(int rhs) {

this.value += rhs;

}

public void add(double rhs) {

this.value += rhs;

}

// etc...

}

Using method overloading, we may succinctly represent add for many different input types, without changing the name of the method. Thus - the caller remains agnostic to the particular implementation they’re calling, having such picked up intuitively based on the arguments provided:

public class Program {

public static void main(String args[]) {

Calculator calculator = new Calculator();

// Infers 1 is type 'int', resolves to first implementation

calculator.add(1);

// 1.5 is type 'double', resolves to second implementation

calculator.add(1.5d);

System.out.println(calculator.value);

}

}

Outputs:

2.5

This is fantastic for reducing ‘burden’ on the programmer - they need not remember different aliases for each add implementation. I’d also argue that it’s a much cleaner, more intuitive way to represent code (or interfaces thereof) - it just feels right semantically.

So lets try transferring this to Rust. Much like above, we’ll define a simple Calculator struct (remember: Rust isn’t traditional OO!), with an add method for int and float types (or the closest equivalent in Rust that works in this example) respectively:

struct Calculator {

value: f64

}

impl Calculator {

fn new() -> Self {

Self { value: 0.0 }

}

fn add(&mut self, rhs: i32) {

self.value += f64::from(rhs)

}

fn add(&mut self, rhs: f64) {

self.value += rhs

}

}

fn main() {

let mut calculator = Calculator::new();

calculator.add(1);

calculator.add(1.5);

println!("{}", calculator.value);

}

Looks good right? Let’s try compiling the above:

error[E0592]: duplicate definitions with name `add`

--> src/main.rs:14:5

|

10 | fn add(&mut self, rhs: i32) {

| --------------------------- other definition for `add`

...

14 | fn add(&mut self, rhs: f64) {

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ duplicate definitions for `add`

For more information about this error, try `rustc --explain E0592`.

Oh dear! Unlike Java, Rust seems to be unable to tell the two apart. Or so it seems… So why does this happen?

Overloading in Rust

As we all know - Rust is an incredibly opinionated language. One such opinion, or design decision, was that traditional method overloading shouldn’t be supported. Why? Well, it makes sense really, considering the Trait-based programming approach Rust applies. As per their 2015 blog post on the trait system:

Overloading. Rust does not support traditional overloading where the same method is defined with multiple signatures. But traits provide much of the benefit of overloading: if a method is defined generically over a trait, it can be called with any type implementing that trait. Compared to traditional overloading, this has two advantages:

First, it means the overloading is less ad hoc: once you understand a trait, you immediately understand the overloading pattern of any APIs using it.

Second, it is extensible: you can effectively provide new overloads downstream from a method by providing new trait implementations.

Beyond their rationale above (which is sound - especially the second), I strongly suspect part of the reason was simplification of compile-time overload resolution. Overload resolution is the process of resolving (looking up and substituting/linking) elided method calls to the appropriate function based on its inputs/arguments. Check out an example here (for C++).

Traits, by virtue of their nature, implicitly support the notion of overloading, and are naturally able to express such (as we’ll see shortly). Rust already provides resolution and Monomorphization of traits (and associated functions) in its compilation pipeline. So why bother complicating things?

Example: From/Into

This approach to overloading is utilized within a plethora of Rust core library traits. Take Into for example:

fn main() {

let a: i64 = 1.into();

let b: f64 = 1.into();

}

Here, during compilation, each into() invocation resolves to the appropriate Into trait implementation, inferred from the type of the let expression on the left-hand-side. Here, the types of our let expressions are i64 and f64 respectively.

Both i64 and f64 implement Into<isize>:

// Below is an example: Into<T> is automatically implemented for types that implement From<T>

// See:

// https://doc.rust-lang.org/src/core/convert/mod.rs.html#704

// https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/convert/trait.Into.html!

impl Into<i64> for isize {

fn into(value: isize) -> i64 {

...

}

}

impl Into<f64> for isize {

fn into(value: isize) -> f64 {

...

}

}

Which is trivially resolved to the appropriate ABI by the compiler:

// Resulting MIR (Mid-Level Intermediate Representation - ala. portable intermediary format)

fn main() -> () {

let mut _0: ();

let _1: i64;

scope 1 {

debug a => _1;

let _2: f64;

scope 2 {

debug b => _2;

}

}

bb0: {

_1 = <i32 as Into<i64>>::into(const 1_i32) -> [return: bb1, unwind continue];

}

bb1: {

_2 = <i32 as Into<f64>>::into(const 1_i32) -> [return: bb2, unwind continue];

}

bb2: {

return;

}

}

Et Voila: Overloading!

Moving On - Rusty Overloading Design Pattern

So, in observing the above, we can see how to go about implementing Overloading within Rust. Let’s continue with our Calculator example set out earlier. Changing tactics, let’s re-implement using the Rusty idioms described earlier:

We’ll first start by defining our ‘overloadable methods’, or functionality, in it’s own separate trait. In this case, the add method. Remember: Traits describe behaviours (or collections of behaviours) - in this case, a series of operations that may be performed on a number. Thus, in line with it’s behaviour, we name the trait Arithmetic, after the mathematical definition:

trait Arithmetic<D> {

fn add(&mut self, rhs: D);

// More arithmetic methods to be defined

}

Given this trait, or behaviour, we may then implement it for our Calculator struct:

impl Arithmetic<i32> for Calculator {

fn add(&mut self, rhs: i32) {

self.value += f64::from(rhs);

}

}

impl Arithmetic<f64> for Calculator {

fn add(&mut self, rhs: f64) {

self.value += rhs;

}

}

Giving us the final code:

struct Calculator {

value: f64

}

impl Calculator {

fn new() -> Self {

Self { value: 0.0 }

}

}

trait Arithmetic<D> {

fn add(&mut self, rhs: D);

}

impl Arithmetic<i32> for Calculator {

fn add(&mut self, rhs: i32) {

self.value += f64::from(rhs);

}

}

impl Arithmetic<f64> for Calculator {

fn add(&mut self, rhs: f64) {

self.value += rhs;

}

}

Now, when calling calculator.add(...), Rust will be able to infer the correct method implementation during compilation, by virtue of Trait Resolution!

fn main() {

let mut calculator = Calculator::new();

calculator.add(1);

calculator.add(1.5);

println!("{}", calculator.value);

}

Outputs:

2.5

Awesome! We’ve finally got our overloaded implementation of add()!

Going Further

In reality, we’d implement the operator traits defined within core::ops for our arithmetic, rather than define our own interface re-implementing theirs. This comes with the added benefit of being able to use built-in aliases for the corresponding operators. I.e. rather than call calculator.add(...), we’d simply use calculator += ... instead!

use core::ops::AddAssign;

impl AddAssign<i32> for Calculator {

fn add_assign(&mut self, rhs: i32) {

self.value += f64::from(rhs);

}

}

impl AddAssign<f64> for Calculator {

fn add_assign(&mut self, rhs: f64) {

self.value += rhs;

}

}

Changing our final code to:

use core::ops::AddAssign;

struct Calculator {

value: f64

}

impl Calculator {

fn new() -> Self {

Self { value: 0.0 }

}

}

impl AddAssign<i32> for Calculator {

fn add_assign(&mut self, rhs: i32) {

self.value += f64::from(rhs);

}

}

impl AddAssign<f64> for Calculator {

fn add_assign(&mut self, rhs: f64) {

self.value += rhs;

}

}

fn main() {

let mut calculator = Calculator::new();

// Woo! No more .add()

calculator += 1;

calculator += 1.5;

println!("{}", calculator.value);

}

Additional to this, there’s several other improvements that can be made. We can, in fact, utilize Rust’s powerful Generic Programming capacities, coupled with behaviourally-driven idioms, to define add_assign for any type that can be converted to f64, reducing our boilerplate even further:

impl<T> AddAssign<T> for Calculator where f64: From<T> {

fn add_assign(&mut self, rhs: T) {

self.value += f64::from(rhs);

}

}

In doing this, Rust automatically generates implementations of AddAssign for all types that convert to f64. This changes our final code to:

use core::ops::AddAssign;

struct Calculator {

value: f64

}

impl Calculator {

fn new() -> Self {

Self { value: 0.0 }

}

}

impl<T> AddAssign<T> for Calculator where f64: From<T> {

fn add_assign(&mut self, rhs: T) {

self.value += f64::from(rhs);

}

}

fn main() {

let mut calculator = Calculator::new();

calculator += 1;

calculator += 1.5;

println!("{}", calculator.value);

}

Note: The compiler should pick up on the un-needed

frominvocation forAddAssign<f64>and optimize it out - It’s pretty smartNote 2: Be aware of Monomorphization and code-bloat using the above approach